Launched in 1918, HMS Dunedin had been in commission without a break when war began in September 1939. In the twenties and thirties she had been part of the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy, spending her time sailing around the Pacific, even helping out when an earthquake struck Napier in New Zealand in 1931. She returned to England in 1937 where she served at Portsmouth as a Boys Sea Training Ship.

Launched in 1918, HMS Dunedin had been in commission without a break when war began in September 1939. In the twenties and thirties she had been part of the New Zealand Division of the Royal Navy, spending her time sailing around the Pacific, even helping out when an earthquake struck Napier in New Zealand in 1931. She returned to England in 1937 where she served at Portsmouth as a Boys Sea Training Ship.

When the Fleet mobilised for war at the end of August 1939, Dunedin was allocated to the 12th Cruiser Squadron based on Kirkwall for service on the Northern Patrol.

Conditions were cold and rough for the mostly reservist crew as Dunedin was charged with intercepting merchant ships using the northern routes to go to or from Germany. Release from these harsh and bitter days came in January 1940 when she left the Northern Patrol for a short spell in Portsmouth before going to Bermuda to join the Americas and West Indies Station. For the next nine months, Dunedin patrolled the Caribbean, visiting every island and intercepting German blockade-runners and French Vichy ships. With HMS Trinidad she was involved without avail in getting a number of French warships including the Carrier Bearn to join the Free French. They did however stay in the West Indies and were thus denied to the Germans. Her biggest success was the capture of the 5,600-ton German merchant ship Hanover off San Domingo. Hanover was subsequently taken into the Royal Navy and was converted into the first Escort Aircraft Carrier, and although sunk after only a short career proved the use of Escort Carriers in the protection of convoys.

On her return to the Clyde in September 1940, Dunedin underwent degaussing and ammunitioning before moving in October to Portsmouth for anti-invasion duties. Captain Lovatt took over from Captain Lambe, who was appointed Assistant Director of Plans in the War Cabinet offices. Dunedin undertook a number of tasks over the coming months, including convoy duty as far as Freetown in Sierra Leone. On Christmas Day, 1940 as part of the escort to convoy WS5A, with HMS Berwick and HMS Bonaventure, Dunedin was involved in action against the German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper. The action was inconclusive, with both Berwick and Hipper taking damage, but Hipper was driven off and the convoy escaped with only minimal damage.

On her return to the Clyde in September 1940, Dunedin underwent degaussing and ammunitioning before moving in October to Portsmouth for anti-invasion duties. Captain Lovatt took over from Captain Lambe, who was appointed Assistant Director of Plans in the War Cabinet offices. Dunedin undertook a number of tasks over the coming months, including convoy duty as far as Freetown in Sierra Leone. On Christmas Day, 1940 as part of the escort to convoy WS5A, with HMS Berwick and HMS Bonaventure, Dunedin was involved in action against the German heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper. The action was inconclusive, with both Berwick and Hipper taking damage, but Hipper was driven off and the convoy escaped with only minimal damage.

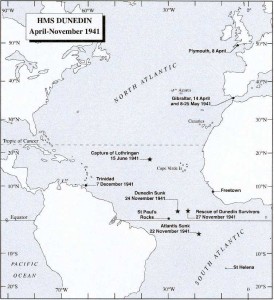

Dunedin left England on 8th April 1941 never to return. She spent the last eight months of her life on the South Atlantic Station.

Much of Dunedin’s movements were dictated during this time by the intelligence gained by the Admiralty through the breaking of the Germans’ Enigma code. In June, the code-breakers at Bletchley Park were reading German naval Enigma traffic with remarkable speed and in the aftermath of the sinking of the Bismarck the Admiralty turned its attention to German supply ships stationed in the Atlantic. Among them was Lothringen, a tanker thought to have been ready to supply the Bismarck and her escort the Prinz Eugen, and capable of supplying U-boats.

In a joint operation with the carrier HMS Eagle, Dunedin was dispatched on 29th May to search for an enemy supply ship (not known at the time to be the Lothringen), reported as being somewhere in the region of 25 degrees North, 34 degrees West. After extensive searching, Eagle’s Swordfish aircraft spotted the tanker on 15th June and Dunedin, with one boiler out of action, made best speed to the scene. Dunedin found Lothringen damaged (from attacks by the Swordfish) but still afloat as the Merchant Navy crewmembers had refused to scuttle her.

In a joint operation with the carrier HMS Eagle, Dunedin was dispatched on 29th May to search for an enemy supply ship (not known at the time to be the Lothringen), reported as being somewhere in the region of 25 degrees North, 34 degrees West. After extensive searching, Eagle’s Swordfish aircraft spotted the tanker on 15th June and Dunedin, with one boiler out of action, made best speed to the scene. Dunedin found Lothringen damaged (from attacks by the Swordfish) but still afloat as the Merchant Navy crewmembers had refused to scuttle her.

When Eagle arrived later in the evening, Dunedin had the situation well in hand and the Lothringen was ready to be steamed to Bermuda. This was an important capture. Not only did it deny the Germans vital oil supplies for their U-boats, but also important Enigma material was found where it had fallen behind a filing cabinet in the wireless room.

When Eagle arrived later in the evening, Dunedin had the situation well in hand and the Lothringen was ready to be steamed to Bermuda. This was an important capture. Not only did it deny the Germans vital oil supplies for their U-boats, but also important Enigma material was found where it had fallen behind a filing cabinet in the wireless room.

Dunedin spent the next few months sailing many hundred of miles in the South Atlantic, calling at Freetown several times as well as St Helena and Bathurst.

In November 1941, Dunedin was involved in another Enigma-inspired operation. The Admiralty had gleaned from Enigma decrypts that the Germans were planning an operation to attack shipping near Cape Town, involving four U-boats, an armed merchant raider (Atlantis) and a supply ship (Python). HMS Devonshire, HMS Dorsetshire, and Dunedin were ordered independently to track them down.

On 22nd November Devonshire came upon U-126 and Atlantis. She sank Atlantis but stayed far enough away from U-126 to avoid being attacked and reported en clair that there were survivors in the water. On 24th November Python came to help U-126, who was towing the boats from Atlantis towards South America.

On the afternoon of the same day, U-124, commanded by Jochen Mohr, was on its way to rendezvous with Python. Near St Paul’s Rocks, 900 miles west of Freetown, just south of the Equator, Mohr sighted Dunedin to his north east sailing a north west course. He therefore hauled out to the west to lie in wait for Dunedin. But Dunedin’s lookout spotted U-124’s periscope around 12.50pm and the Captain changed course to set off in pursuit. But because of U-124’s change of course west, Dunedin was now unwittingly pulling away from U-124. When Mohr surfaced again he saw Dunedin disappearing into the distance, at least 4,000 yards away. He nevertheless fired three torpedoes. Incredibly, from this distance, two were on target even though Dunedin was steaming 17 knots, and was under constant wheel.

On the afternoon of the same day, U-124, commanded by Jochen Mohr, was on its way to rendezvous with Python. Near St Paul’s Rocks, 900 miles west of Freetown, just south of the Equator, Mohr sighted Dunedin to his north east sailing a north west course. He therefore hauled out to the west to lie in wait for Dunedin. But Dunedin’s lookout spotted U-124’s periscope around 12.50pm and the Captain changed course to set off in pursuit. But because of U-124’s change of course west, Dunedin was now unwittingly pulling away from U-124. When Mohr surfaced again he saw Dunedin disappearing into the distance, at least 4,000 yards away. He nevertheless fired three torpedoes. Incredibly, from this distance, two were on target even though Dunedin was steaming 17 knots, and was under constant wheel.

The two torpedoes hit within seconds of each other, at around 1326 GMT, the first striking amidships, wrecking the main wireless office, the second further aft, probably near the officers’ quarters. The first hit sent the ship lurching to starboard, the second caused even greater damage dismounting the after 6in gun, and blowing off the starboard screw. Immediately men began to abandon ship, jumping over the side to the Carley floats and any available debris. Dunedin turned on her beam ends and sank in about seventeen minutes. According to U-124’s war diary, Mohr moved in before Dunedin sank and fired a fourth torpedo, but missed.

Shortly after the sinking, U-124 surfaced and circled the survivors. The U-boat was on the surface for no more than ten minutes before diving but while the survivors waited to see what was intended, and as a spontaneous act of defiance, they sang “There will always be an England”.

In the water, up to two hundred and fifty men from a ship’s complement of nearly five hundred struggled to haul themselves on to Carley floats and anything that would float. Seven Carley floats got away.

In the water, up to two hundred and fifty men from a ship’s complement of nearly five hundred struggled to haul themselves on to Carley floats and anything that would float. Seven Carley floats got away.

For the next seventy-eight hours, their numbers dwindled in the equatorial heat. Some men died of their injuries sustained when the torpedoes hit, some died of exhaustion, some went insane, others drowned, and some were bitten and killed by vicious fish. Sharks were an ever-present menace.

When, in the late afternoon of 27th November, the Nishmaha, a US merchant ship en route from Takoradi to Philadelphia, happened upon the six remaining Carley rafts, only seventy-two men were still alive. Five would subsequently die before the Nishmaha reached Trinidad, leaving just sixty-seven out of the original complement of around five hundred.

When, in the late afternoon of 27th November, the Nishmaha, a US merchant ship en route from Takoradi to Philadelphia, happened upon the six remaining Carley rafts, only seventy-two men were still alive. Five would subsequently die before the Nishmaha reached Trinidad, leaving just sixty-seven out of the original complement of around five hundred.

The story of HMS Dunedin was a notable absence from the history books until our research. She might not have been the most famous ship of World War II, but she played a key part and suffered terrible losses.