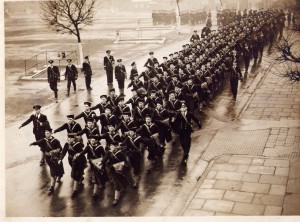

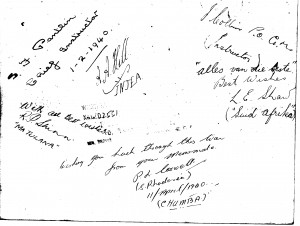

In the middle is a late 1939 photo of “conscripts” at Butlins holiday camp in Skegness, which had been converted into a training camp. Somewhere in this picture is RP Shinn, whose signature is on the back of the photo (right).

Biographical Notes

One of several Rhodesians on board, Ronald Shinn served in Dunedin for about two years before she was hit. He was on deck at his gun when the torpedoes hit.

Later, he joined HMS Onslaught, a destroyer, and sailed with the Russian convoys in extremely cold and dangerous weather.

After four years away from home, he was sunk a second time when his troopship en route to Cape Town was attacked by dive-bombers. Once more he found himself on a raft, but he and other survivors were picked up within an hour. He married then returned to sea and survived the war.

In April 2010, the family of Ronald Shinn discovered some fascinating new papers. Ronald’s son-in-law, Mick Mckenna, wrote to the Dunedin Society with the news:

Ronald Shinn had an older brother, George, who was one of a number of Rhodesians who, in World War II, were attached to and then fought with the British Army’s King’s Royal Rifle Corps.

Over the last Easter weekend and in a scene reminiscent of an old film, George’s grand-daughter arrived at our home with a packet of his medals and other bits and pieces of old wartime memorabilia. She asked if I could tell her what it all meant.

In the packet I found a newspaper cutting from what would have been the Bulawayo Chronicle, probably dated about January 1942. The cutting reproduces the letter sent to his parents by Ron on his return to England after the sinking of the Dunedin. It was an exciting find because no one, not even his wife, has ever seen this account before and, because he was always so reluctant to talk of that tragedy, no one really knew exactly what he had experienced.

I thought you may wish to circulate the account amongst your members. If so, please feel free. I attach a copy of the cuttings. Because of the way the newspaper was printed, they are out of sequence but the whole story is there. To assist anyone with tired eyes I have typed out the account in Microsoft Word.

Another interesting fact we have learned from these cuttings was that he, and presumably some others from the Dunedin, returned to England from Trinidad on the SS Duchess of York. Two years later, in July 1943 and after four years service, he was given leave to go home (and get married). He was sailing on that very same ship as part of a convoy to Cape Town via Freetown, Sierra Leone when she was bombed and sunk off Spain. He eventually got home via Casablanca. Fortunately, his bride was still waiting.

And here’s Ronald Shinn’s account, as originally published in the Bulawayo Chronicle, probably in January 1942:

THIRST, MADNESS AND DEATH ON

SURVIVORS’ RAFTS

————————-

BULAWAYO MAN’S TALE OF DREADFUL DAYS

AFTER DUNEDIN DISASTER

“Dear Mum and Dad, – Here I am again in England after a very eventful voyage which ended in my returning to England without the old Dunedin” writes Ronald Shinn, a young Bulawayo man who was one of the 63 survivors of HMS Dunedin which was torpedoed in mid-Atlantic on December 18, and who spent several dreadful days and nights adrift, first on a plank and then on a raft until rescued by an American ship.

Immediately he reached shore safely he cabled his parents, Mr. and Mrs. P.E. Shinn of Bulawayo, and as soon as he could do so wrote an account of his adventures.

Mr Shinn joined the Navy under the auspices of the Bulawayo branch of the Navy League. He was educated at Milton High School and at St. George’s College, Salisbury and before the war was employed at Cement.

AFTER GERMAN RAIDER.

“I suppose you are wondering how I managed to make myself one of the 63 survivors out 481 ship’s company,” he wrote to his parents. “We went out in search of a German raider operating in the middle of the Atlantic and after four days steaming from our base we were about 1000 miles from the African and American coasts. The look-out spotted a mast ahead, and half an hour afterwards there was a lovely bang followed by another a couple of seconds later. Smoke, water and debris went sky high and the ship took a nasty list.

“Then things started. We started getting the rafts off, with everybody slipping and sliding on the fuel oil which had been spread all over the deck by the explosion. Once the rafts were over everybody swarmed over the side and made a dash for them but, as you may imagine, there wasn’t enough room on the rafts for everyone, so some had to go down and they did.

“The fuel oil took a few, because although it calmed the sea it was nasty swimming through, especially when you swallowed a mouthful.

“I couldn’t get a show in anywhere, as all the rafts were crowded so I had to find some other means of support and after a little swimming about came across a wooden: gangway which was just big enough to take my weight. That’s where I stopped and watched the ship gradually go down. Before she went to the bottom the U-boat came to the surface to have a look round, then went down again. When the ship disappeared we got down to business. All the rafts got together and it wasn’t long before we had connected them with lengths of rope.

NO WATER

“Our first discovery was that there wasn’t any water in the bottles and we had only half a box of biscuits among us. Well, it wasn’t long before it was dark. Being the first night everybody saw rockets, lights and all kinds of things that weren’t there. The first thing that greeted me in the early hours as I sprawled on my gangway was the fin of a shark which cut the water very nicely all around me. I just about fell off my gangway with fright and I am sure my hair stood on end in spite of all the fuel oil in it.

“By the afternoon one man had died from burns, so that gave me the chance to get on to a raft. I took it quickly and likely. When the next night fell things took a turn for the worse and a couple of fellows got light headed and we had to be cruel to be kind and give them a good thumping. During the night there was a short shower and we all put out our tongues to get a little moisture. Next day another man died on our raft and another in the afternoon from drinking sea water. That afternoon we managed to pick up a mast and sail from one of our broken boats. We cut the sail into pieces to shield ourselves from the sun and tied the mast to the raft with a pair of pants fluttering from the top.

COMPLETELY MAD

“Things got on the move again the following night. Fellows were diving off, saying they were going to make some tea or going for a couple of beers. Not all the hammering in the world would hold them. The next morning there were a few more short, including two officers whom we didn’t expect to return because they went completely mad and were trying to bite everyone.

But in spite of our troubles we did have fate on our side because that night it rained again. It rained cats and dogs and we caught enough water to fill our bottles and then we had a drink as the water ran off the canvas, which made a big difference to the outlook.

“During the day the men kept seeing aircraft, convoys, bottles of beer all round. Well, when it came to 4 p.m. and someone said he saw smoke on the horizon we just gave him a pathetic look. But after a little investigation we could see masts and superstructures so we started to paddle – and did we paddle! Was she German, Vichy French, British or American? We wondered, but it didn’t stop us paddling.

“She kept stopping every now and again and we couldn’t make out why. When we got close we were very relieved to see the Stars and Stripes. On board everything was waiting for us in the dining room and, ye gods, did that coffee taste good! The crew gave up their beds to the wounded and the rest of us just went to sleep on a flat part of the deck without any persuasion.

FIVE MORE DIED

“The reason for the queer behaviour of the ship was that there were two more rafts ahead of us that we didn’t know of and she was picking them up. The following morning we were very sorry to hear that five more of our survivors had died during the night.

“From then until we arrived at Trinidad the Americans couldn’t do enough for us. They were a real cheerful crowd, which made a big difference”

After three days at Trinidad the survivors were taken back to England on board the Duchess of York.